Dissecting Attention

Dissecting Attention: What Happens When You Share Different Parts of the Attention Mechanism

I’ve been trying to get into machine learning, and while reading through papers, I stumbled across something that puzzled me. The paper was ALBERT by Google Research - “A Lite BERT”1 that uses parameter sharing tricks to reduce model size without hurting performance. But here’s what I couldn’t wrap my head around: how does sharing the same attention weights across every layer not break everything?

Why This Shouldn’t Work: What We Know About Attention

To understand why ALBERT’s success is so surprising, we need to establish what attention heads are supposed to do, at least according to current heuristics. Years of interpretability research have revealed that different attention heads learn remarkably specialized functions:

- Syntactic heads focus on grammatical relationships - subject-verb agreement, modifier-noun pairs, and dependency parsing structures

- Positional heads attend to relative positions - previous tokens, next tokens, or tokens at fixed distances

- Semantic heads capture meaning relationships - coreference resolution, entity relationships, and thematic roles

- Task-specific heads emerge during fine-tuning to handle particular downstream objectives

Perhaps most importantly, attention heads across layers form hierarchical processing pipelines. Early layers typically focus on local syntactic patterns (adjacent words, simple grammatical relationships), while deeper layers capture longer-range semantic dependencies and abstract relationships. This hierarchical specialization is foundational to how we understand transformer learning - it’s why we expect different layers to need different attention parameters.

The conventional wisdom, supported by papers like “What Does BERT Look At?” and “A Structural Probe for Finding Syntax in Word Representations,” suggests that forcing layers to share attention weights should collapse this hierarchy and destroy the model’s ability to build compositional representations.

ALBERT’s Counterintuitive Success

This is what makes ALBERT’s results so puzzling. ALBERT employs aggressive parameter sharing across transformer layers, what the paper refers to as cross-layer parameter sharing. The same attention weights (queries, keys, and values) are reused across all 12 layers. It even experiments with sharing the FFN weights as well to surprisingly similar results. There are a few other optimizations like factorizing the embedding so that the first hidden layer is independent of the embedding size, as well as using only masked language modeling (MLM) as a task for training since it was demonstrated that this training strategy was more effective than the original BERT paper’s strategy of using both MLM and next sentence prediction. However, since these are less important to the attention weights being shared, I’ll limit my discussion of these changes.

The result? ALBERT-base matches or exceeds BERT-base performance while using only 18M parameters instead of 110M - a 83% reduction. When they tested different sharing strategies, they found:

- Sharing only attention parameters: minimal performance loss (~1-2%)

- Sharing only feed-forward parameters: moderate performance loss (~2-3%)

- Sharing both attention and FFN parameters: larger but still acceptable loss (~3-4%)

The fact that attention sharing works better than FFN sharing directly contradicts our understanding. Feed-forward networks are often viewed as “parameter storage” - collections of learned facts and transformations. If anything should be shareable, it should be these fact-storage components, not the dynamic attention mechanisms that supposedly need to specialize for different levels of abstraction. Yet we see the opposite dynamic here. Note that sharing both attention and FFN parameters creates an architecture that is basically one ‘real’ layer getting passed the information over and over again–a step back towards the RNN structure that transformers evolved from. The mystery still remains that sharing attention parameters results in little to no performance loss. The paper explains this as possible due to redundancy in transformer layers, where similar features are learned from between the layers.

The Broader Landscape of Parameter Sharing

ALBERT wasn’t alone in challenging the assumptions about parameter sharing. Other research, some earlier, and some later, has shown that sharing attention components works across multiple contexts:

Multi-Query Attention (MQA) and Grouped-Query Attention (GQA)2 share key and value projections across attention heads within the same layer. In MQA, all heads share a single set of key and value parameters while maintaining separate queries. GQA uses partial sharing - groups of heads share keys and values. Both achieve significant computational savings with minimal performance loss, suggesting that the KV components contain more redundancy than previously assumed. This is for a decoder model, unlike ALBERT which is an encoder, suggesting that this may be something to do with attention itself rather than architectural differences.

LiSA (Learnable Sharing Attention)3 revealed something even more fundamental: attention weights are remarkably similar across transformer layers, with most layers showing JS divergence scores below 0.05. They found that when training from scratch with direct weight sharing across layers, models maintained lossless performance. Crucially, while attention patterns were similar across layers, the Q, K, and V matrices themselves captured different features - suggesting that similar attention patterns can emerge from different underlying representations. This is also used on a decoder model.

These results point to a fundamental pattern: sharing certain attention components works consistently across different architectural choices and training regimes. This isn’t a quirk of one particular model or training procedure - it appears to be revealing something deeper about how attention mechanisms function.

The Puzzle Deepens: A Semantic Chain Hypothesis

Here’s what caught my attention about this pattern: if ALBERT shows that full attention sharing between layers works, and MQA/GQA show that KV sharing between heads works, what about other combinations? Does sharing different attention components lead to different qualities of attention–that is, what effects does sharing the keys, values, and weights respectively have on attention metrics?

This possibility suggests something interesting: that the key and value components of attention might encode more stable, semantic information than we previously understood. Rather than learning layer-specific or head-specific transformations, they might be capturing token-level semantic properties that remain consistent across different levels of abstraction.

I call this the Semantic Chain Hypothesis: as suspected by the literature, different components of the attention mechanism (K, Q, V) may have distinct semantic roles, but what if some components may be encoding stable token relationships while others handle dynamic, context-specific processing. If this is true, then I hypothesize that:

- Keys (K) might encode “what information is semantically available” - relatively stable across contexts depending on tokenization. Perhaps these represent the information content of a specific token.

- Values (V) might encode “what information to extract” - also potentially stable, representing an orthogonal element of information content in a specific token.

- Queries (Q) might encode “what we’re looking for” - more dynamic and context-dependent.

This hypothesis would explain why KV sharing works so well across different architectures, and why Q parameters seem to need more specialization. Embeddings of tokens and their KV weights may be creating a sematic chain that is a coherent object of semantic analysis.

The Question: Which Parts of Attention Can Be Shared?

Interesting enough for a theory, so I decided to probe deeper. If different attention components have distinct semantic roles, then sharing them should produce different effects on how attention behaves. By systematically sharing different combinations of K, Q, and V parameters across layers, we might be able to decode what each component actually contributes to the attention mechanism.

My hypothesis was that these components would show different sharing patterns:

- Some components might be highly shareable (suggesting stable, semantic roles)

- Others might require specialization (suggesting dynamic, context-dependent roles)

- The specific patterns of sharing effects would reveal the underlying structure of attention

What follows is my experimental investigation into which parts of attention can be shared, and what these sharing patterns tell us about how attention really works.

Experimental Setup

To test my hypothesis, I built a simple BERT-style transformer and trained it on IMDB sentiment analysis. The experimental design was straightforward but rigorous: share different combinations of attention parameters (K, Q, V) across all layers and measure how this affects both task performance and attention behavior. I also cribbed pretty hard from Peter Bloem’s excellent set of notes regarding attention and transformers4:

To ensure statistical reliability, I ran each condition for 30 epochs across 15 different random seeds and performed comprehensive statistical analysis (ANOVA, power analysis, t-tests). This approach let me distinguish real effects from random variation.

I measured four metrics to capture different aspects of attention behavior:

- Test Accuracy: Does sharing hurt the model’s ability to learn the task?

- Attention Entropy: How focused vs. distributed is the attention? (Higher = more spread out across tokens)

- Attention Sparsity: What percentage of attention weights are near zero? (Higher = more selective attention)

- Head Specialization: How different are attention heads from each other? (Higher = more diverse functions)

The choice of metrics was deliberate. Accuracy tells us about functional impact, while the attention metrics reveal mechanistic changes. Entropy and sparsity capture complementary aspects of attention distribution - entropy measures how evenly attention is spread, while sparsity measures how much attention is concentrated on a few tokens. Head specialization reveals whether sharing forces heads to become more similar to each other.

However, I know that there are probably a lot more rigorous ways of describing and teasing out the behavior of attention in the interpretability literature. I wanted to run this experiment partially to get myself equipped with transformers in general, but also to begin to try and ask more interesting questions about them. I’d like to return to this question once I’ve learned a little (or a lot) more about transformer architecture and the current tooling in mech interp.

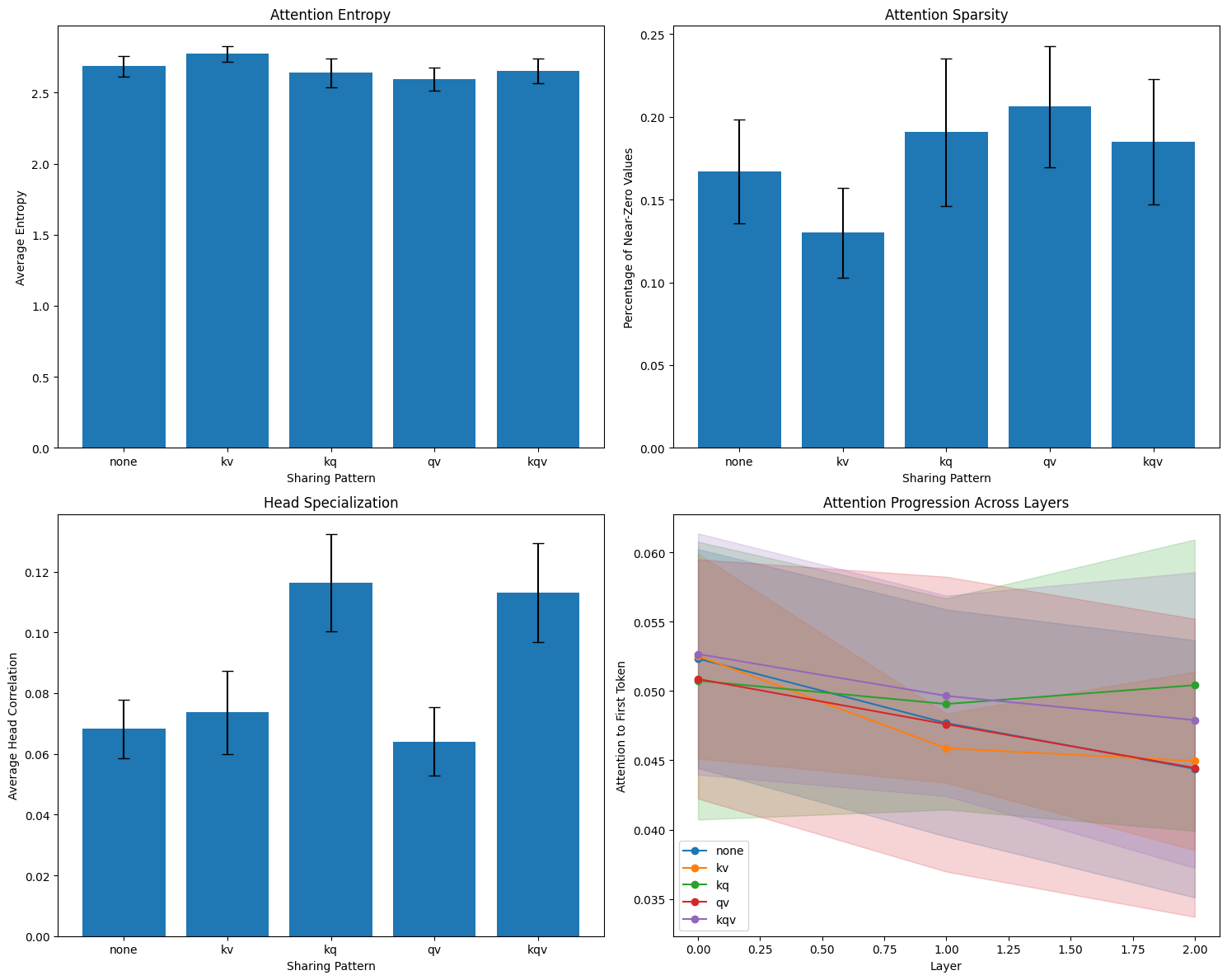

Experiment 1: Combined Sharing Patterns

First, I tested combinations of attention components: KV, KQ, QV, and KQV sharing compared to no sharing baseline. This experiment was designed to see which combinations work and identify interaction effects between components.

The Performance Surprise

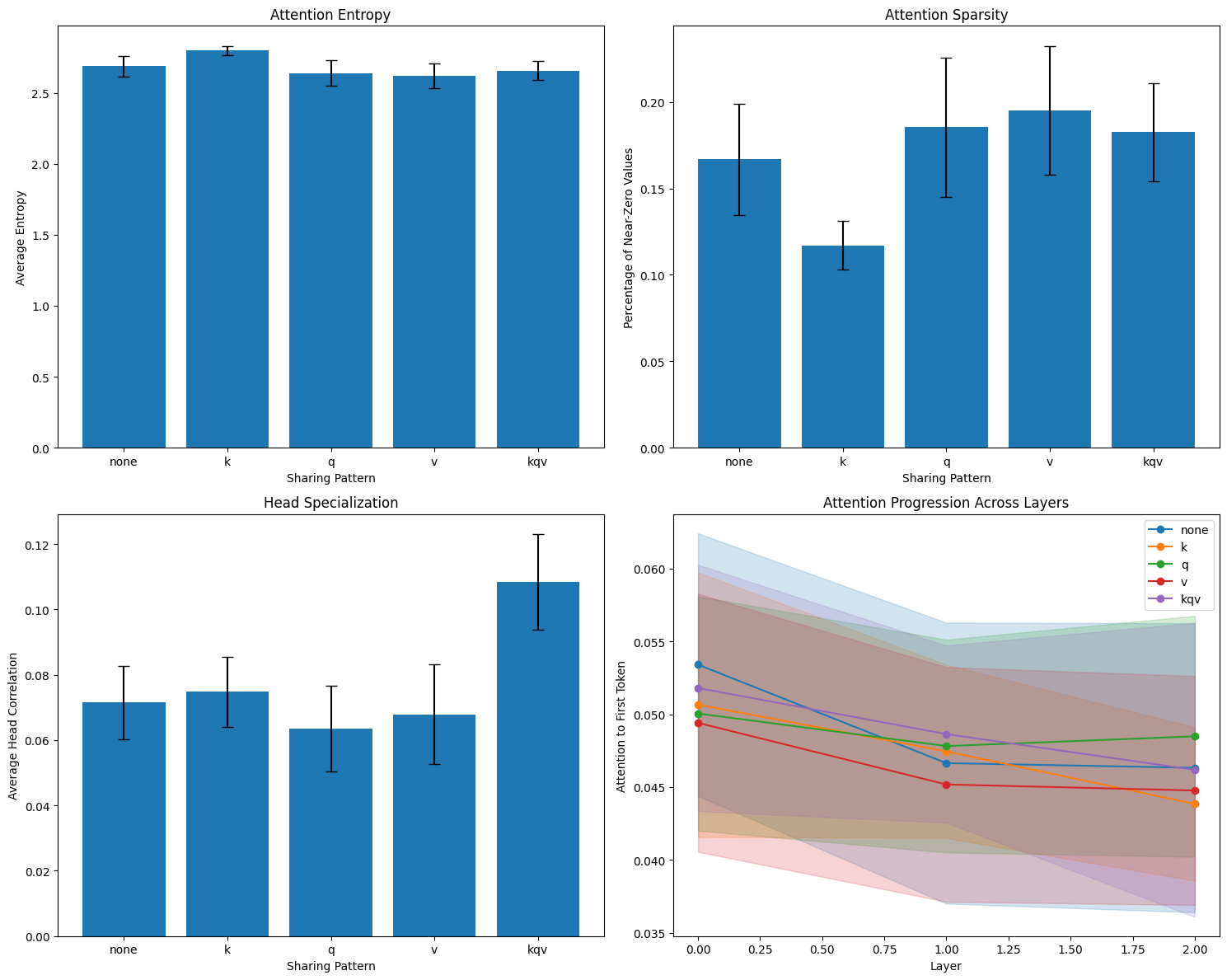

The first result was immediate: performance was identical across all conditions. Every sharing pattern achieved the same validation accuracy curve, converging to approximately 82% accuracy regardless of which attention components were shared.

The result has interesting implications. For there to be absolutely no difference is still surprising. It suggests that for this task, there’s massive redundancy in the attention mechanism - the model can achieve the same functional performance even when forced to reuse attention parameters across all layers. However, I should note another important caveat: IMDB sentiment analysis might not be demanding enough to reveal performance differences. The bulk of learning in small models often happens in the embedding layer (which contains most parameters), so the attention mechanism might not be the bottleneck for this particular task. This may just be a really easy question that could be solved with just a clever embedding layer, and no attention needed at all. I discuss this more in the limitations and future experiments section.

Attention Patterns Tell a Different Story

While performance remained constant, the attention patterns themselves were dramatically different across sharing conditions. This is where the real interesting patterns emerged:

KV Sharing produced the most distributed attention patterns - significantly higher entropy and lower sparsity. Models with shared keys and values spread their attention more broadly across input tokens rather than focusing intensely on specific positions.

QV Sharing showed the opposite effect - slightly lower entropy and higher sparsity, suggesting more focused attention patterns. However, these effects were smaller and less consistent than KV sharing.

KQ Sharing had a qualitatively different impact, primarily affecting head specialization. Models with shared queries and keys showed significantly higher head correlation , meaning attention heads became much more similar to each other.

KQV Sharing (ALBERT-style) combined these effects, showing both the head similarity effect and moderate changes in attention distribution. I also measured attention progression across layers - how attention to individual tokens changes as you go deeper into the model - thinking this might reveal interesting abstraction patterns. But to be completely honest, I can’t make heads or tails of those results. The patterns seem noisy and I’m not sure if there’s a signal there or if I need better analysis tools. I’ll definitely need to do more research into current interpretability studies and what the state of the art in studying attention heads looks like.

Statistical Validation

The statistical analysis confirms these observations: Accuracy Metrics: No significant differences - so sharing at least doesn’t hurt performance Entropy: Significant differences with KV (p=0.0015) and QV (p=0.0042) showing significant deviations from baseline Sparsity: Significant differences with KV (p=0.0024) and QV (p=0.0052) effects Head Specialization: Significant differences with KQ (p<0.0001) and KQV (p<0.0001) showing reduced head diversity

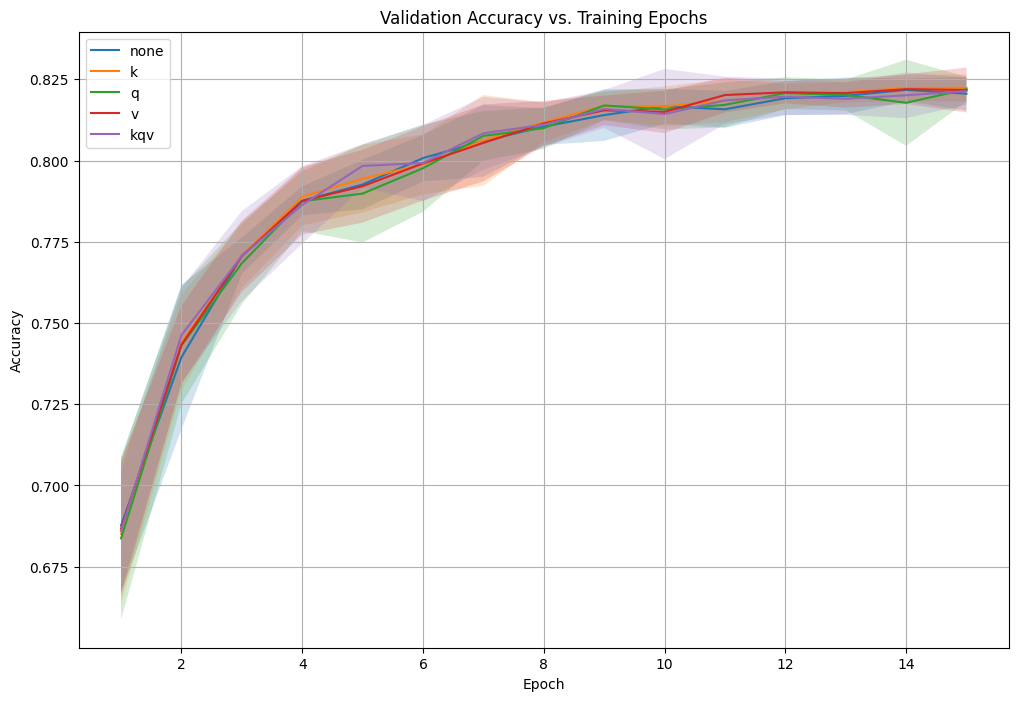

Experiment 2: Individual Component Analysis

To isolate which components were driving these effects, I tested sharing individual attention parameters: K-only, Q-only, V-only, plus KQV as a reference point.

Key Sharing: The Distribution Driver

The results clearly identified K sharing as the primary driver of attention distribution effects. Models with shared keys consistently showed:

- Highest attention entropy

- Lowest attention sparsity

- Robust effects across all statistical tests

This pattern was remarkably consistent - whenever keys were shared (K-only, KV, KQ, KQV conditions), attention became more distributed. This suggests that keys play a special role in determining attention breadth.

Query and Value Sharing: Subtler Effects

Q sharing and V sharing showed much weaker individual effects:

- V sharing produced slight focusing effects (lower entropy, higher sparsity), but these weren’t statistically robust across all tests

- Q sharing had minimal impact on entropy and sparsity metrics, though it contributed to head similarity when combined with other components

The Emergent Head Specialization Effect

Here’s where things get interesting: KQV sharing produced massive reductions in head specialization, but individual K, Q, and V sharing had minimal effects on head diversity. This suggests an emergent interaction - sharing all attention parameters creates constraints that force heads to become similar, but sharing individual components allows heads to maintain diversity through the unshared parameters.

Statistical Evidence

The statistical analysis provides robust confirmation of these patterns. For Experiment 2 (individual components), the results were particularly clear:

Performance remains unaffected: No significant differences in test accuracy across any sharing condition (ANOVA: F=0.262, p=0.9016), confirming that attention parameter sharing doesn’t impair the model’s ability to learn sentiment classification. K sharing drives attention distribution changes: Key sharing produced the strongest and most statistically robust effects. For entropy, K sharing showed a massive effect size of 2.031 with perfect statistical power (t=-5.374, p<0.0001). Similarly, for sparsity, K sharing had an effect size of 2.014 with perfect power (t=5.330, p<0.0001). These are exceptionally large effects in attention research, indicating that keys play a fundamental role in determining attention breadth.

V sharing shows weaker but significant effects: Value sharing produced smaller but still significant effects on both entropy (p=0.0315) and sparsity (p=0.0395), though with moderate effect sizes (0.857 and 0.817 respectively) and insufficient statistical power, suggesting these effects need additional validation.

Q sharing shows minimal individual impact: Query sharing alone had no significant effects on entropy, sparsity, or head specialization, with small effect sizes and insufficient power across all metrics. KQV sharing uniquely affects head specialization: Only the full KQV sharing condition significantly reduced head specialization (p<0.0001) with a very large effect size of 2.833. Individual components (K, Q, V) showed no significant effects on head diversity, confirming that the head similarity effect emerges only when multiple components are shared simultaneously.

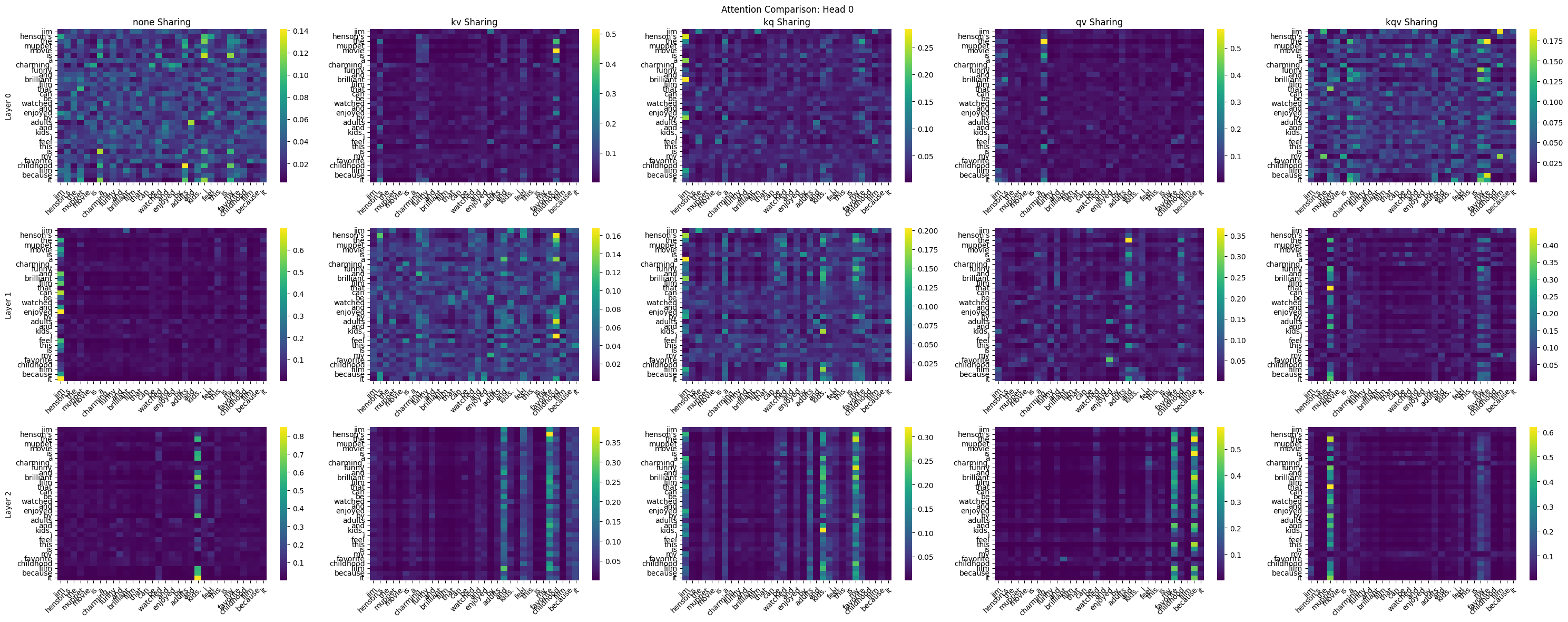

Visual Evidence: Attention Heatmaps

The attention visualizations provide compelling qualitative evidence for these quantitative findings. Looking at the same sentence processed by different sharing conditions:

“jim henson’s the muppet movie is a charming, funny and brilliant film that can be watched and enjoyed by adults and kids. i feel this is my favorite childhood film because it”

Head 0 shows clear structural differences across conditions:

- No sharing: Focused attention on specific tokens with clear patterns

- KV sharing: More diffuse attention spread across multiple tokens, with more bright bands of highly attentive tokens.

- KQ sharing: Similar overall structure but different intensity patterns

- QV sharing: Sharp focus on specific tokens

- KQV sharing: Simplified patterns with less complexity

This pattern largely holds across heads, with some exceptions. This is not the greatest source of evidence, especially compared to the statistical evidence. But it is the prettiest. I have the other head heatmaps in the colab notebook for those who wish to peruse them, but I’d like to go back over this with more state of the art attention interpretability techniques, like TransformerVis and the like5.

Interpreting the Attention Patterns

These results reveal distinct functional roles for attention components:

Keys as Semantic Availability Signals: The strong distributing effect of K sharing suggests that keys encode “what information is available for attention.” When keys are shared across layers, all layers have access to the same semantic availability signals, leading to broader attention patterns. This might force the model to develop more general-purpose attention strategies rather than layer-specific focus patterns.

Queries as Context-Specific Selectors: The fact that Q sharing has minimal individual effects, but contributes to head similarity when combined with K sharing, suggests queries encode “what we’re looking for” in a more context-dependent way. Queries might need more specialization to maintain head diversity.

Values as Information Extractors: V sharing shows weak focusing effects, which might indicate that shared value transformations create slight bottlenecks that force more selective attention. This will need more statistical tests to verify though.

Interaction Effects: The emergence of head similarity only when multiple components are shared reveals that attention heads maintain diversity through complementary specialization across K, Q, and V. Remove too many degrees of freedom, and heads collapse into similar functions.

These statistical results provide compelling evidence that different attention components have distinct and separable functions, with keys serving as the primary drivers of attention distribution patterns. These experiments provide compelling evidence for the hypothesis and for semantic chains. The results suggest that attention components do have separable semantic functions:

Keys (K) as Semantic Availability Encoders: Keys appear to encode stable semantic availability information that can be shared across layers without performance loss. However, K sharing creates more distributed attention patterns, which represents an interesting tradeoff. While diffuse attention patterns often correlate with higher training loss in some contexts, they also tend to facilitate easier transfer learning and generalization. This suggests that K sharing may help models learn more general, transferable concepts rather than task-specific attention strategies.

Values (V) as Selective Information Extractors: Value sharing shows the most intriguing effects - opposite to those of K sharing, with a tendency toward more focused attention patterns. However, these effects require additional statistical power to confirm robustly. The focusing effect of V sharing might indicate that shared value transformations create bottlenecks that force more selective attention, potentially leading to more specialized feature extraction.

Queries (Q) as Context-Specific Selectors: Queries seem to require more specialization to maintain head diversity, suggesting they encode more context-specific selection criteria that resist sharing across layers.

Emergent Interaction Effects: The fact that head specialization effects only emerge when multiple components are shared simultaneously reveals that attention heads maintain diversity through complementary specialization across K, Q, and V parameters.

The consistency of these patterns across different sharing combinations, and their alignment with findings from ALBERT, LiSA, and MQA/GQA architectures, suggests we’re observing fundamental properties of attention mechanisms rather than task-specific artifacts.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several important limitations should be acknowledged. In these small models, most parameters reside in the embedding layer, which dwarfs the attention weights in size. It’s possible that the embedding layer handles most of the computational work, allowing attention to vary significantly without impacting performance. Additionally, testing on only sentiment analysis provides limited evidence - a comprehensive evaluation would require diverse benchmarks like GLUE.

However, the fact that attention sharing works across different model scales (BERT at ~250M parameters, LLaMA at 4B+ parameters) and architectures (encoder and decoder models) suggests these findings reflect fundamental properties rather than scale-specific artifacts.

Future experiments that would strengthen these findings include:

- Larger model validation: Testing on models where attention parameters constitute a larger fraction of total parameters

- Cross-architecture sharing: Exploring architectures with shared KV across both layers AND heads, potentially creating extremely efficient attention mechanisms

- Mechanistic interpretability: Using sophisticated tools like TransformerLens to dive deeper into the mechanistic differences between sharing conditions

- Comprehensive task evaluation: Testing across diverse benchmarks to ensure findings generalize beyond sentiment analysis

- Transfer learning studies: Investigating whether the more general concepts potentially learned through K sharing actually improve transfer performance

Most importantly, the massive redundancy revealed by unchanged performance across all sharing conditions indicates that current attention mechanisms may be significantly over-parameterized. This opens exciting possibilities for more efficient architectures that selectively share components based on their semantic roles.

I’d also like to say that I am a total neophyte in the field of interpretability and ai–if this is totally wrong, and my approach is unfounded, I am happy to accept that. This blog post and experiment is just my try at pursuing a thought I found interesting, and I hope it was an interesting read for others as well.